Prisoner's Health Project, 1974 - 1978

In the early 70s, Dr. Fine's focus was on prison reform. He helped establish the Security Ward within San Francisco General Hospital which meant prisoners could get proper medical and mental health care without being transferred to a state facility. Hospital staff also recieved more extensive training and established security measures to provide the necessary care to jail and psychiatric patients. In 1968, the MCHR conducted a survey in San Francisco and Alameda county jails that showed prison conditions to be horrible. This was followed by a 1969 report conducted by Diane Feinstein-led Special Advisory Committee that exposed even worse conditions. It wasn't until 1973 that a federal court judge - Judge Schnacke, ruled that jail conditions violated the Eighth Ammendment of the Constitution and constituted "cruel and unusual punishment". This was the cue for Dr. Fine - then Medical Chief of the Hospital Security Ward and Dr. Gerald Frank - former medical chief for San Francisco jails - to come up with a proposal to improve conditions in county jails. The proposal resulted in a grant with the goals of improving and providing more comprehensive health care programs and services to inmates along with increasing trained staff.

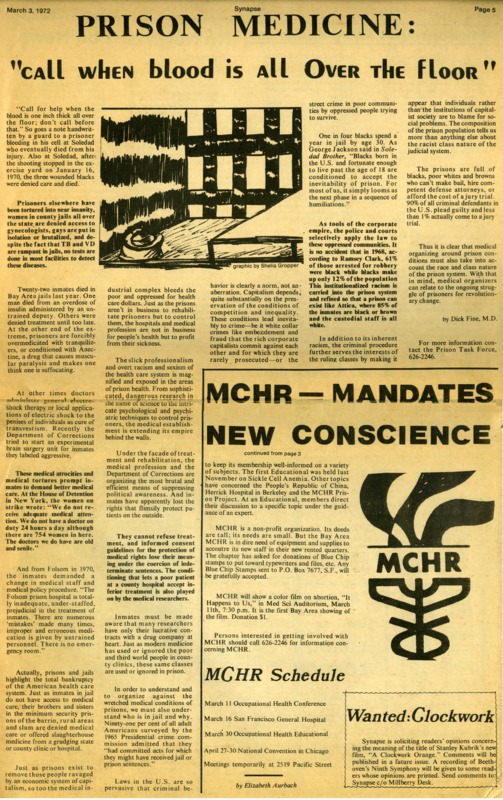

Dr. Fine wrote Prison Medicine: "call when blood is all Over the floor" for UCSF's student newspaper Synapse, in 1972. His article described the horrific treatment of prisoners in Bay Area county jails.

"Call for help when the blood is one inch thick all over the floor; don't call before that." So goes a note handwritten by a guard to a prisoner bleeding in his cell at Soledad who eventually died from his injury.

Dr. Fine echoes the mission of the MCHR to raise public awareness of issues of discrimination and inequity within health care systems in his closing paragraphs which read:

The prisons are full of blacks, poor whites and browns who can't make bail, hire competent defense attorneys, or afford the cost of a jury trial. 90% of all criminal defendants in the U.S. plead guilty and less than 1% actually come to a jury trial.

Thus it is clear that medical organizing around prison conditions must also take into account the race and class nature of the prison system. With that in mind, medical organizers can relate to the ongoing struggle of prisoners for revolutionary changes.

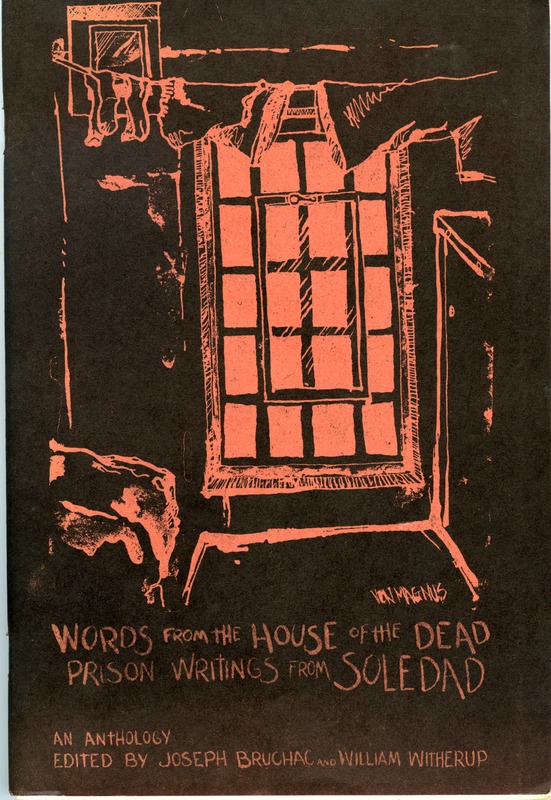

Words from the House of the Dead, Prison Writings from Soledad: An Anthology was composed of anonymous writings by prisoners that were smuggled out of the Soledad prison. Edited by poet and publisher Joseph Bruchac and late poet and playwright William Witherup, this collection of writings demonstrated the humanity of prisoners. In Bruchac's words,

Instead of the angry, hate-the-pigs, kill-the-honky voices I had been conditioned to expect from prison writers I was hearing men talk of flowers, of children [...] Men being able to laugh and cry just like you an me. I was teaching a Freshman English class the day I recieved the book; we had been reading a section of Soul on Ice. And I did what every English teacher does sooner or later, I asked my class how they really felt about Cleaver, about a man who was a criminal, a confessed criminal. And there were some who said, honestly, that they found it hard if not impossible to sympathize with a man in prison. Then I began to read some of the poems from The 6:15 Unlock and I passed the book, with hand colored drawings, with bits of flowers and pigeon feathers pasted to the pages, around the room. For the first time that day some of those students began to realize that their perceptions of men in prison had been as incorrect in their way as my ideas had been in mine. Both of us made the mistake of underestimating the greatness of the human soul. (Bruchac, Words from the House of the Dead, Prison Writings from Soledad)

![Health PAC Bulletin - Prison Health; Vol. 53 Sept. 1973 [cover]](https://ucsf.libraryhost.com/files/square/8e913a3ee1ba65f085edcb25eade2c30bf7d02c6.jpg)